Compact disc/digital, 2020, IMED 20165, empreintes DIGITALes, 4580, avenue de Lorimier, Montréal (Québec) H2H 2B5, Canada; telephone: +1/514 526-4096; email: info@empreintesDIGITALes.com; https://empreintesDIGITALes.com

Reviewed by Arian Bagheri Pour Fallah

Lisbon, Portugal

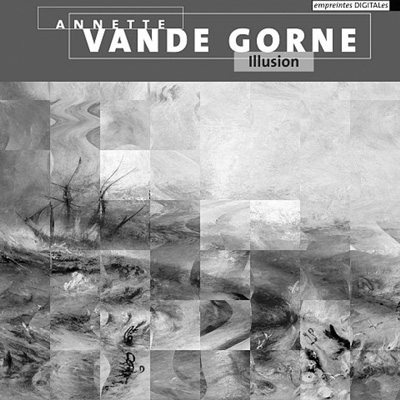

Slavers

Throwing overboard the Dead and Dying—Typhoon coming on, better known as The

Slave Ship (1840), is among J. M. W. Turner’s finest paintings, and one of

the most recognizable visual artworks of the romantic movement. Fused with les automatistes-founder, the painter Paul-Émile Borduas’ L’étoile noire (1957), it greets listeners of Annette Vande Gorne’s latest acousmatic venture, Illusion, in the form of Luc Beauchemin’s cover art, Seule issue (2020). The level

of intertextuality is broad. Beauchemin’s title hints

at necessity. The cover art’s contrasting frames of references, too, provide an

air of calamity. It is difficult, one may say impossible, to free one image

from the other, or to brush aside the many implications of these whispers,

these overtones in the context of here and now, in the wake of the COVID-19

pandemic, but also the ethical, as well as economic state of the world today.

In spite of a seemingly absent narrative, these specters endure, however,

throughout Illusion, at times by virtue of the omnipotence of sounds,

and at others, through the performers’ material and gestural presence.

Slavers

Throwing overboard the Dead and Dying—Typhoon coming on, better known as The

Slave Ship (1840), is among J. M. W. Turner’s finest paintings, and one of

the most recognizable visual artworks of the romantic movement. Fused with les automatistes-founder, the painter Paul-Émile Borduas’ L’étoile noire (1957), it greets listeners of Annette Vande Gorne’s latest acousmatic venture, Illusion, in the form of Luc Beauchemin’s cover art, Seule issue (2020). The level

of intertextuality is broad. Beauchemin’s title hints

at necessity. The cover art’s contrasting frames of references, too, provide an

air of calamity. It is difficult, one may say impossible, to free one image

from the other, or to brush aside the many implications of these whispers,

these overtones in the context of here and now, in the wake of the COVID-19

pandemic, but also the ethical, as well as economic state of the world today.

In spite of a seemingly absent narrative, these specters endure, however,

throughout Illusion, at times by virtue of the omnipotence of sounds,

and at others, through the performers’ material and gestural presence.

Déluges et autres péripéties (2014-5), the most recent endeavor on this album, operates from a singular, base leitmotif: “We await destruction.” Replacing the ambiguity of the image with the certainty of the word, Vande Gorne chooses to walk in the glinting footsteps of poet Werner Lambersy, whose voice is one of the three employed in the piece. Least subject to the manipulations pertinent to musique concrète, Lambersy’s voice is used mainly to wend an otherwise umbrous or disquieting narrative. It is spoken using a narrator’s voice, akin to Jean Négroni’s role in Apocalypse de Jean by Pierre Henry. The piece is, in form, an art song. With a length of half an hour, its effectiveness depends on the listener’s willingness to follow along. For it is punishing throughout, singular in this respect in Vande Gorne’s repertoire, times more threatening in character than Impalpables while matching, if not exceeding, the fervor of the opera Yawar Fiesta.

Vande Gorne’s implacable art song is a far cry from Turner’s gracious, albeit troubling, landscape. Where Turner transfigures, Vande Gorne echoes the dread, supporting a horrific poem, in her own words, “with horrific sounds.” Not only is the piece texturally and emotionally unrelenting, the implementation of the voice in reverse can only be described as miasmic, rendering it vicious in ways contradicting contemporary acousmatic aesthetics. In this respect, the vicious narrative has few parallels in the greater electroacoustic repertoire, among them, Michel Chion’s Sanctus, from his early work, and the mass Requiem (1973), an equally demented endeavor rich in extended vocal experiments and, most of all, spoken words.

Yet, does this bring the piece closer to Borduas and les automatistes? The art song is dedicated to Francis Dhomont, whose rapport with spoken words is exemplary within the broader acousmatic tradition. As per the majority of acousmatic works, it makes use of the fixed medium, and is designed for a 16-channel setup. This places it well away from the inclinations of les automatistes. Declarations such as “It seemed as if our future were set in stone,” from the scandalous 1948 manifesto, Refus Global, for which Borduas and les automatistes are most remembered, here are not points of departure for unrest but very much Vande Gorne’s aspirations. For her as a composer, fixity remains both an aesthetic and an ontological necessity. Hers is, in other words, neither a romantic, but even more prominently, nor a revolutionary concern. In her own words: “I do not have a romantic vision of art” (CMJ 36(1): 10–22). The automatic and the improvisatory are, in her view, contrasted with architecture and organization—with mastery over one’s time. This is what she also shares with Chion. His notion of sons fix´es [fixed sounds] Vande Gorne deems to be “correct,” in relation to fixing time. Having said that, it may be useful to question the nature of this “mastery” over time.

Today, acousmatic music remains part medium and part listening strategy. In the first instance, it involves fixed media, with scattered examples of hybrid (live with fixed elements) media, which often employ of small groups or individual performers. It is also as a fixed media that notions such as sons fix´es find immediate meaning. In other words, the further one moves away from fixed into hybrid media, notions such as sons fix´es become more difficult to follow. For one thing, the live instrument or electronics can disallow any immediate control outside that of the performer. Hence, the implicit decision of most composers in the acousmatic tradition to produce works more often in the former category. As regards listening strategies, it is fair to say that many listeners are unfamiliar with either reduced listening or spectromorphology. The select few who are familiar would struggle to find any reciprocity, strictly speaking, between the listening strategies and the notion of fixed sounds. So, does this “mastery” point to anything except an aesthetic proclivity?

The two iterations of the third and last piece included in Illusion, Faisceauxare concluded respectively, in fixed and hybrid media. Whereas the former is designed for fixed stereo medium, the latter is accompanied with a pianist. Within the acousmatic tradition, collaborative works, regardless of the nature of the collaborations, rank among the strongest. For example, Gilles Gobeil’s best works, including his individual recordings, are those involving composer-performer René Lussier. Simon Emmerson’s duets with Lol Coxhill outrival the composer’s “fixed” works. Barry Schrader’s recent collaboration with Wadada Leo Smith has not only exposed his works, for the first time, to a wider audience, it is furthermore aesthetically varied in ways that are not true of his earlier output. The list goes on. And the hybrid variant of Faisceaux is no exception. Albeit suffering from what has already been discussed regarding hybrid media, namely that the fixed sounds are accompanied with a narrow number of instruments or performers, in this case, one pianist, the hybrid rendition is one of the most commanding works included in Illusion.

It is evocative but also pulsating and alive. The performer’s presence is able to disrupt, even if briefly, the moribund, idealistic narrative evoked by the fixed component. It is a refreshing take, compared with similar ventures of Vande Gorne into evocative sound worlds, such as Terre (1991) or the included fixed-medium variant, and although using instrumentation that is as of now depleted by composers time and again, it manages to stand out in a selection dominated by fixed media. What is evident, from Faisceaux but also the other examples noted above, is that the alleged mastery over time is, more than anything, an aesthetic qualifier. While true to some degree that a narrative temporally fixed also allows the composer to have more immediate control over the output, this is by and large incidental and furthermore subordinate to the primary function of the fixed medium which is to predefine the work aesthetically.

Finally, it is the spirit of Arsène Souffriau that roams Illusion. The album’s opener, Au-delà du réel, with which I find apropos to close this review, is dedicated to the enigmatic composer. Obliquely reminiscent of Vande Gorne’s own Métal (1983), the piece pyramids percussive and instrumental resonance into hypnotic spectra, while conniving at performative gestures. Compared with the former, its use of spectral mobility, pronounced by oscillations and rotations primarily, is a lot more vivid, thereby evolving faster with a magnetizing effect on the listener. As per the other dedications on Illusion, it is a material and not a merely symbolic celebration. The piece employs sound-objects from a rare collection gathered by Souffriau, catalogued according to materials, ranges, and frequencies.

It is as if instruments become doorways to the tenebrous. His self-described “instrumental” piece, Incantation (N'sien ufo d'ra) (1981), for ondes martenot, tcheng, and three percussionists, albeit with a modus operandi different from that of Vande Gorne, in which both a score and performers are present, achieves analogous aesthetic results. The piece’s backstory is also one that pertains to the discussion on composer and performer reciprocity in the acousmatic strand. Allegedly, another version was intended by the composer but was never realized, due to the performers’ unwillingness to learn “the unusual notation of the score.” Vande Gorne may not be a romantic, yet the acousmatic tradition with which she identifies, has always been prone to idealism. Acousmatic music, which, rather interestingly, positioned itself in contrast to concert-hall music, appears all the more today to suffer from the same set of predicaments besetting musique spectrale, once openly described by Grisey also as an aesthetic. And this is Illusion’s weakness as well as source of its partial strength. Acousmatic music, as aesthetic, is recognizable strictly due to the fixity of vision shared by its practitioners, and in that also, it cannot proceed forward unless opening up the creative space for performers, stressing reciprocity and collaboration.